History of the University of Pennsylvania

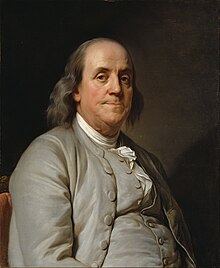

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. Its history began with in 1740, when a group of Philadelphians organized to erect a great preaching hall for George Whitefield, a traveling evangelist.[1] The building was designed and constructed by Edmund Woolley and was the largest building in Philadelphia at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time in which it was preached.[2]: 26 In the fall of 1749, Ben Franklin circulated a pamphlet, "Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia".[3] On June 16, 1755, the College of Philadelphia was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction.[4]: 13

18th century[edit]

In 1740, a group of Philadelphians organized to erect a great preaching hall for George Whitefield, a traveling evangelist.[5] The building was designed and constructed by Edmund Woolley and was the largest building in Philadelphia at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time in which it was preached.[2]: 26 The preaching hall was initially intended to also serve as a charity school, but a lack of funds forced plans for the chapel and school to be suspended.

According to Franklin's autobiography, he first had the idea to establish an academy in 1743, writing, "thinking the Rev. Richard Peters a fit person to superintend such an institution." Peters declined a casual inquiry.[6] In the fall of 1749, Franklin circulated a pamphlet, "Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia".[7] The 1749 proposal was seen as innovative at the time, and Franklin organized 24 trustees from among Philadelphia's leading citizens, the first such non-sectarian board in the nation. At the first meeting of the board of trustees on November 13, 1749, the issue of where to locate the school was a prime concern. Although a lot across Sixth Street from the old Pennsylvania State House, later renamed and famously known since 1776 as Independence Hall, was offered without cost by James Logan, its owner, the trustees realized that the building erected in 1740 by Edmund Woolley for George Whitefield,[8] which was still vacant, was an even more preferable site.

Penn's library began in 1750 with a donation of books from cartographer Lewis Evans. Twelve years later, then-provost William Smith sailed to England to raise additional funds to increase the collection size. Benjamin Franklin was one of the libraries' earliest donors and, as a trustee, saw to it that funds were allocated for the purchase of texts from London.

On August 13, 1751, the Academy of Philadelphia, using the great hall at 4th and Arch Streets, was established and began taking in its first secondary students. A charity school also was chartered on July 13, 1753,[4]: 12 by the intentions of the original donors, although it lasted only a few years.

On June 16, 1755, the College of Philadelphia was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction; its first classes were taught in the same building, in many cases to the same boys who had already graduated from The Academy of Philadelphia.[4]: 13 All three schools shared the same board of trustees and were considered part of the same institution.[9] The first commencement exercises were held on May 17, 1757.[4]: 14

The University of Pennsylvania considers itself the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, though this is contested by Princeton and Columbia Universities.[note 1] It also considers itself the first university in the United States with both undergraduate and graduate studies, though that claim is also contested. Unlike the other colonial colleges that existed in 1749, including Harvard, William & Mary, Yale, and the College of New Jersey, Franklin's new school did not focus exclusively on educating clergy. He advocated what was then an innovative concept of higher education, which taught both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living and performing public service. The proposed program of study could have become the nation's first modern liberal arts curriculum, although it was never implemented because Anglican priest William Smith, who became the first provost, and other trustees strongly preferred the traditional curriculum.[11][12] In the 1750s, roughly 40 percent of Penn students needed lodging since they came from areas in the British North American colonies that were too far to commute, or were international students.[13] Before the completion of the construction of the first dormitory in 1765, out of town students were typically placed with guardians in the homes of faculty or in suitable boarding houses.[14][15] Jonathan and Philip Gayienquitioga, two brothers of the Mohawk Nation,[16] were recruited by Benjamin Franklin to attend the Academy of Philadelphia,[17] making them the first Native Americans at Penn when they enrolled in 1755.[18]

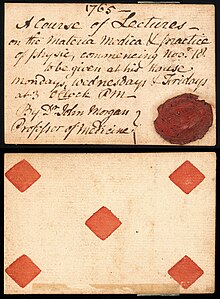

The 1765 founding of the first medical school in America[19] made Penn the first institution to offer both "undergraduate" and professional education. Moses Levy, the first Jewish student, enrolled in 1769.[20] In 1765, the campus was expanded by opening of the newly completed dormitory run by Benjamin Franklin's collaborator on the study of electricity using electrostatic machines and related technology and Penn professor and chief master Ebenezer Kinnersley.[note 2] Kinnersley was designated steward of the students in the dormitory and he and his wife were given disciplinary powers over the students and supervised the cleanliness of the students with respect to personal hygiene and washing of the students' dirty clothing.[21][22] Even after its construction, however, many students sought living quarters elsewhere, where they would have more personal freedom, resulting in a loss of funds to the university. In the fall of 1775, Penn's trustees voted to advertise to lease the dormitory to a private family who would board the pupils at lesser cost to Penn.[23] In another attempt to control the off-campus activities of the students, the trustees agreed not to admit any out-of-town student unless he was lodged in a place which they and the faculty considered proper.[13] As of 1779, Penn, through its trustees, owned three houses on Fourth Street, just north of the campus's new building with the largest residence located on the corner of Fourth and Arch Streets.[24][13]

When the British abandoned Philadelphia during the Philadelphia campaign in the American Revolutionary War, College Hall, the college's only building at the time,[note 3] served as the temporary meeting site of the Second Continental Congress from July 7 to 20, 1778,[25] briefly establishing Penn's campus as one of the early capitals of the United States.[26][27]

In 1779, not trusting then provost William Smith's Loyalist tendencies, the revolutionary State Legislature created a university, and in 1785 the legislature changed name to University of the State of Pennsylvania.[9][note 4] The result was a schism, with Smith continuing to operate an attenuated version of the College of Philadelphia. The 1779 charter represented the first American institution of higher learning to take the name of "University".[28][29] In 1791, the legislature issued a new charter, merging the two institutions into a new University of Pennsylvania with twelve men from each institution serving on the new board of trustees.[9]

19th century[edit]

In 1802, the university moved to the unused Presidential Mansion at Ninth and Market Streets, a building that both George Washington and John Adams had declined to occupy while Philadelphia was the nation's capital.[4]

Among the classes given in 1807 at this building were those offered by Benjamin Rush, a professor of chemistry, medical theory, and clinical practice who was also a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence, member of the Continental Congress,[30][31] and surgeon general of the Continental Army.[32] Classes were held in the mansion until 1829 when it was demolished. Architect William Strickland designed twin buildings on the same site, College Hall{{refn|group=note|The "College Hall" on the 9th Street campus was the second of three Penn buildings named "College Hall", which was initially located on the original campus at 4th and Arch streets and served as the capital of the United States temporarily for ten days, and Medical Hall (both 1829–1830), which formed the core of the Ninth Street Campus. Joseph M. Urquiola, School of Medicine class of 1829, was the first Latino,[33][34][35] and Auxencio Maria Pena, School of Medicine class of 1836, was the first South American[36] to graduate from Penn.

In 1849, following formation of Penn's Eta chapter[note 5] of Delta Phi by five founders and 15 initiates,[37] Penn students began to establish residential fraternity houses. Since Penn only had limited housing near campus and since students, especially those at the medical school, came from all over the country, the students elected to fend for themselves rather than live in housing owned by Penn trustees. A number chose housing by pledging and living in Penn's first fraternities, which included Delta Phi, Zeta Psi, Phi Kappa Sigma, and Delta Psi.[38] These first fraternities were located within walking distance of 9th and Chestnut Street since the campus was located from 1800 to 1872 on the west side of Ninth Street, from Market Street on the north to Chestnut Street on the south. Zeta Psi Fraternity was located at the southeast corner of 10th Street and Chestnut Street, Delta Phi was located on the south side of 11th Street near Chestnut Street, and Delta Psi was located on the north side of Chestnut Street, west of 10th Street.[39]

After being located in downtown Philadelphia for more than a century, the campus was moved across the Schuylkill River to property purchased from the Blockley Almshouse in West Philadelphia in 1872, where it has since remained in an area now known as University City. The new campus and its associated fraternities centered on the intersection of Woodland Avenue, 36th Street, and Locust Street. Among the first fraternities to build near the new campus were Phi Delta Theta in 1883 and Psi Upsilon in 1891. By 1891, there were at least 17 fraternities at the university.[40]

Penn hosted the nation's first university teaching hospital in 1874; the Wharton School, the world's first collegiate business school, in 1881; the first American student union building, Houston Hall, in 1896;[41] and the only school of veterinary medicine in the United States that originated directly from its medical school, in 1884.[42][43] William Adger, James Brister, and Nathan Francis Mossell in 1879 were the first African Americans to enroll at Penn. Adger was the first African American to graduate from the college at Penn (1883),[44] and when Brister graduated from the School of Dental Medicine (Penn Dental) (class of 1881), he was the first African American to earn a degree at Penn.[45] Tosui Imadate was the first person of Asian descent to graduate from Penn (College [46] Class of 1879).[47] Mary Alice Bennett and Anna H. Johnson were in 1880 the first women to enroll in a Penn degree-granting program and Bennett was the first woman to receive a degree from Penn, which was a PhD.[48][49][33]

From its founding until construction of the Quadrangle Dormitories, which started construction in 1895, the university largely lacked university-owned housing with the exception of a significant part of the 18th century. A significant portion of the undergraduate population commuted from Delaware Valley locations, and a large number of students resided in the Philadelphia area.[50] The medical school, then with roughly half the students, was a significant exception to this trend as it attracted a more geographically diverse population of students.[51][52]

George Henderson, president of the class of 1889, wrote in his monograph distributed to his classmates at their 20th reunion that Penn's strong growth in acreage and number of buildings it constructed over the prior two decades (along with a near-quadrupling in the size of the student body) was accommodated by building The Quad.[53] Henderson argued that building The Quad was influential in attracting students, and he appealed for it to be expanded:[54]

And the new buildings? First of all there is need of greater dormitory room. Did you ever live in the "dorms?" Then you do not know what "dorm" life means for college spirit. Several hundred men who live in the same big family have a feeling of common fellowship. Life in the "dorms" develops what our sociologists call a "Solidarity of Responsibility." Men who live there learn to care for the associations that brought them together and that keep them related. And this college spirit they never lose or forget. Some parents, living at a distance, do not like to send their sons to live in a general boarding house. But a dormitory, a University institution, appeals to them, and the boys come and live there. You would scarcely believe it, but when College opened last fall not only were the dormitory rooms over subscribed, but there was a long list of anxious ones, ready to snap up the room of any unlucky fellow who might miss his examinations, and be forced to spend another year at preparatory school grind. So we need the new dormitories, and although they are going up steadily, they might well go up faster.[54]

20th century[edit]

During the first decades of the 20th century, Penn made strides and took an active interest in attracting diverse students from around the globe. Two examples of such action occurred in 1910. Penn's first director of publicity, created a recruiting brochure, translated into Spanish, with approximately 10,000 copies circulated throughout Latin America. That same year, the Penn-affiliated organization, the Cosmopolitan Club, started an annual tradition of hosting an opening "smoker," which attracted students from 40 nations who were formally welcomed to the university by then-vice provost Edgar Fahs Smith (who the following year would start a ten-year tenure as provost)[55][56][57][58][59] who spoke about how Penn wanted to "bring together students of different countries and break down misunderstandings existing between them."[33]

In 1911, since it was difficult to house the international students due to the segregation-era housing regulations in Philadelphia and across the United States, the Christian Association at the University of Pennsylvania hired its first Foreign Mission Secretary, Reverend Alpheus Waldo Stevenson.[60] By 1912, Stevenson focused almost all his efforts on the foreign students at Penn who needed help finding housing resulting in the Christian Association buying 3905 Spruce Street located adjacent to Penn's West Philadelphia campus.[61] By January 1, 1918, 3905 Spruce Street officially opened under the sponsorship of the Christian Association as a Home for Foreign Students, which came to be known as the International Students' House with Reverend Stevenson as its first director.[62]

The success of efforts to reach out to the international students was reported in 1921 when the official Penn publicity department reported[63]

We have an enrollment at the University of 12,000 students, who have registered from every State in the Union, and 253 students from at least fifty foreign countries and foreign territories, including India, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and practically all the British possessions except Ireland; every Latin American country, and most of the Oriental and European nations.

— George E. Nitzsche, 1921[63]

From 1930 to 1966, there were 54 documented Rowbottom riots, a student tradition of rioting which included everything from car smashing to panty raids.[64] After 1966, there were five more instances of "Rowbottoms," the latest occurring in 1980.[64]

By 1931, first-year students were required to live in the quadrangle unless they received official permission to live with their families or other relatives.[51] However, throughout this period and into the early post-World War II period, the undergraduate schools of the university continued to have a large commuting population.[65] As an example, into the late 1940s, two-thirds of Penn women students were commuters.[66]

After World War II, the university began a capital spending program to overhaul its campus, including its student housing. A large number of students migrating to universities under the G.I. Bill, and the ensuing increase in Penn's student population highlighted that Penn had outgrown previous expansions, which ended during the Great Depression era. But in addition to a significant student population from the Delaware Valley, the university continued to attract international students from at least 50 countries and from all 50 states as early as of the second decade of the 1920s.[63][67] Penn Trustee Paul Miller wrote that, in the post-World War II era, "[t]he bricks-and-mortar Capital Campaign of the Sixties...built the facilities that turned Penn from a commuter school to a residential one...."[68] By 1961, 79% of male undergraduates and 57% of female undergraduates lived on campus.[69]

In 1965, Penn students learned that the university was sponsoring research projects for the United States' chemical and biological weapons program.[70] According to Herman and Rutman, the revelation that "CB Projects Spicerack and Summit were directly connected with U.S. military activities in Southeast Asia," caused students to petition Penn president Gaylord Harnwell to halt the program, citing the project as being "immoral, inhuman, illegal, and unbefitting of an academic institution."[70] Members of the faculty believed that an academic university should not be performing classified research and voted to re-examine the university agency which was responsible for the project on November 4, 1965.[70]

The first openly LGBTQ+ organization funded by Penn was formed in 1972 by Kiyoshi Kuromiya, a Benjamin Franklin Scholar and Penn alumnus from the college's class of 1966, when he created the Gay Coffee Hour, which met every week on campus and was also open to non-students and served as an alternative space to gay bars for gay people of all ages.[71]

In 1983, members of the Animal Liberation Front broke into the Head Injury Clinical Research Laboratory in the School of Medicine and stole research audio and video tapes. The stolen tapes were given to PETA who edited the footage to create a film, Unnecessary Fuss. As a result of media coverage and pressure from animal rights activists, the project was closed down.[72]

Penn gained notoriety in 1993 for the water buffalo incident in which a student who told a group of mostly black female students to "shut up, you water buffalo" was charged with violating the university's racial harassment policy.[73]

21st century[edit]

In 2022, some asked for the tenure of Amy Wax, a University of Pennsylvania law school professor to be revoked after she said the country is "better off with fewer Asians."[74][75] In March 2023, Penn announced a first in the United States LGBTQ+ scholar in residence after a $2-million gift.[76]

In October 2023, Penn hosted a Palestinian Writers Conference on campus which was attended by several hundred students, scholars and members of the media. The conference was sponsored by student groups at the university though not by the university itself. Segments of the student body, alumni and the media expressed extreme hostility to the event, in some cases viewing the conference as an affront to their own perspectives in the ongoing Israel/Palestine conflict.[77] While the conference was viewed as a success by its organizers, it contributed to heightened tensions on campus between pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli groups as well as advocates of free speech vs. people concerned with certain forms of expression.[78] After the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel, tensions across university campuses rose across the United States. Certain schools, including Penn, Harvard University and MIT were cited repeatedly in the media for particularly vocal student protests against Israeli military strikes against the civilian populations in Gaza as well as Hamas' violent attack on villages and military outposts just north of the Gaza/Israeli barrier wall.[79] These protests led to increased concerns about anti-Arab and anti-Semitic activities on college campuses. These concerns in turn led to Congressional hearings convening by several conservative Republican congressmen focused on the fears of rising anti-Semitism in the US.

During a hearing before the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce on December 6, when prompted for a "Yes/No" response to a hypothetical situation about protesters "calls for the genocide of Jewish people," Magill replied with nuanced responses to the hypothetical scenario based on the university's codes of conduct and its guidelines for free speech and campus behavior.[80] Magill's response was deemed by certain politicians, external stakeholders and members of the media as tolerant of antisemitism. Significant media pressure, vocal concerns voiced by a number of trustees and threats to suspend donations to the university by several large pro-Israel donors continued to mount.[81] On December 9, President, Liz Magill and the chairman of its board of trustees, Scott L. Bok, resigned from their respective positions.[82] Magill will remain as a tenured member of the Penn Law faculty.[83] Scott Bok later published a letter addressed to the university committee detailing his perspective on the entire situation and his recommendations for university governance going forward.[84]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution. The College of Philadelphia, which became Penn, College of New Jersey, which became Princeton University, and King's College, which later became Columbia College and ultimately Columbia University, all originated within a few years of each other. After initially designating 1750 as its founding date, Penn later considered 1749 to be its founding date for more than a century with Penn alumni observing a centennial celebration in 1849.[10]

- ^ In 1753, a Presbyterian minister without a pulpit, Reverend Kinnersley, was elected Chief Master in the College of Philadelphia, and in 1755 was appointed professor of English and oratory. See Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). "Kinnersley, Ebenezer". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ As Penn moved West, "College Hall" continued to be the name of Penn's headquarters building and now serves as location of "The Office of the President". See "President's Center". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ "...(d) On November 27, 1779, the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania passed an act for the establishment of a University incorporating the rights and powers of the College, Academy, and Charitable School. This was the first designation of an institution in the United States as a University; (e) On September 22, 1785, an act was passed naming the University the University of the State of Pennsylvania..." See "Statues of the Trustees". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Now known at Penn as "St. Elmo's Club" with male and female members."St. Elmo Club". St. Elmo Club. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

References[edit]

- ^ see second footnote 9 in Extracts from the Benjamin Franklin published Pennsylvania Gazette, (January 3 to December 25, 1740) – Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 Archived August 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine "Note: The annotations to this document, and any other modern editorial content, are copyright the American Philosophical Society and Yale University. All rights reserved."

- ^ a b Montgomery, Thomas Harrison (1900). A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co. LCCN 00003240.

- ^ Friedman, Steven Morgan. "A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives". Archives.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Wood, George Bacon (1834). The History of the University of Pennsylvania, from Its Origin to the Year 1827. McCarty and Davis. LCCN 07007833. OCLC 760190902.

- ^ see second footnote 9 in Extracts from the Benjamin Franklin published Pennsylvania Gazette, (January 3 to December 25, 1740) – Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 Archived August 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine "Note: The annotations to this document, and any other modern editorial content, are copyright the American Philosophical Society and Yale University. All rights reserved."

- ^ "Richard Peters". Archives.upenn.edu. January 24, 2022. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Friedman, Steven Morgan. "A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives". Archives.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Extracts from the Pennsylvania Gazette, (January 3 to December 25, 1740) – Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 Archived August 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Penn in the 18th Century, University of Pennsylvania Archives". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ "Gazette: Building Penn's Brand (Sept/Oct 2002)". www.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on November 20, 2005. Retrieved January 25, 2006.

- ^ "Penn's Heritage". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ^ N. Landsman, From Colonials to Provincials: American Thought and Culture, 1680–1760 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), p. 30.

- ^ a b c "Penn in the 18th Century Student Life: A Campus Shared by the College, the Academy, and the Charity School". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ University of Pennsylvania's The Alumni Register, June 1905, article by Isaac Anderson Pennypacker, (Penn College Class of '02) pp. 408–412

- ^ "A Description of Life at the Academy and College of Philadelphia by Student Alexander Graydon, 1811". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs – Akwesasne, NY". www.mohawknation.org. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "History: Native American Studies at Penn | Native American & Indigenous Studies at Penn". Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "History: Native American Studies at Penn". Native American & Indigenous Studies at Penn. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ A Committee of the Society of the Alumni (1894). "Biographical catalogue of the matriculates of the college together with lists of the members of the college faculty and the trustees, officers and recipients of honorary degrees, 1749–1893". Philadelphia: Avil Printing Company. p. 18 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bell, Whitfield J., and Charles Greifenstein, Jr. Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society. 3 volumes, 1997: volume I: pages 80, 90, 154, 339—40; volume II: pages 69, 179; volume III: pages 22, 33, 41, 200–207, 298, 307, 533 (needs to be confirmed as this cite was copied from other Wikipedia entry for Kinnersley)

- ^ "Ebenezer Kinnersley 1711 – 1778". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "October 17, 1775". Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania Minute Books 1768–1779; 1789–1791. Vol. II. College, Academy and Charitable School; University of Pennsylvania. p. 93. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021 – via Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image.

- ^ The Trustees Minutes and a 1779 Plan of the College

- ^ "Meeting Places for the Continental Congresses and the Confederation Congress, 1774–1789". Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "College Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: July 2, 1778 to July 20, 1778". unitedstatescapitals.org. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: The Nine Capitals of the United States". United States Senate. Archived from the original on June 16, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "The University of Pennsylvania: America's First University". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on July 11, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ See also "Statutes of the Trustees". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Renker, Elizabeth M. (1989). "'Declaration–Men' and the Rhetoric of Self-Presentation". Early American Literature. 24 (2): 123 and n. 10 there. JSTOR 25056766.

- ^ Rush, Benjamin (1970) [1948]. George Washington Corner (ed.). The autobiography of Benjamin Rush; his Travels through life together with his Commonplace book for 1789–1813. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- ^ "Benjamin Rush (1746–1813)". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Timeline of Diversity at Penn: 1740–1915". University Archives and Records Center. Penn. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Maxwell, Will J. (ed.). General Alumni Catalogue of the University of Pennsylvania, 1917. University of Pennsylvania General Alumni Society. p. 597.

- ^ Urquiola's March 1829 dissertation Urquiola, Joseph M. (1829). "Essay on Menstruation". Penn Libraries Franklin. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021. was cited in August 2021. See Shepard, Louisa (August 10, 2021). "Two centuries old, a handwritten record of medical education". Penn Today. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Biographical Memoranda Respecting All who Ever Were Members of the Class of 1832. Yale University. 1880. p. 217. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2021 – via Google Books. (note: Venezuela was officially known as Captaincy General of Venezuela, a department of Spain, when Pena was born)

- ^ "Early Fraternities Delta Phi (St. Elmo)". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "Early Penn Fraternities". University Archives and Records Center. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ "Histories of Early Penn Fraternities: Earliest Account of Penn Fraternities". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

excerpted from the diary of George D. Budd (1843–1874) who received his A.B. from Penn in 1862, and LL.B. from Penn Law in 1865.

- ^ "Histories of Early Penn Fraternities". University Archives and Records Center. Penn. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, George E.; Brownlee, David Bruce (2000). Building America's First University: An Historical and Architectural Guide to the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8122-3515-9.

- ^ "Penn Vet | Our History". Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ "Brief History: School of Veterinary Medicine". Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Davis, Heather A. (September 21, 2017). "For the Record: William Adger". Penn Today, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "James Brister". University Archives and Records Center. Penn. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ J. William White, Biography by Agnes Repplier, page 220, The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Houghton Mifflin 1919

- ^ "Tosni Imadate (born 1856), B.S. 1879, portrait photograph". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2021 – via Artstor.

- ^ "Dr. (Mary) Alice Bennett". Changing The Face Of Medicine. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ Ogilvie, Marilyn; Harvey, Joy (2000). The Biographical Dictionary Of Women In Science. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 115. ISBN 0-415-92038-8.

- ^ Baltzell, Digby (1996). Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 253. ISBN 978-1560008309.

- ^ a b Linck, Elizabeth (1990). "The Quadrangle". University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Pieczynski, Denise (1990). "National Crisis, Institutional Change: Penn and the Civil War" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Class Collection". University Archives and Records Center. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ a b George Henderson, Old Penn and Other Universities: A Comparative Study of Twenty Years Progress of The University of Pennsylvania, (U. of Pa. Class of '89) June 1909 Monograph in Penn Archives for Class of 1889: Box 9, Folder 8 (PDF) Archived December 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Penn Chemistry History". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ . New International Encyclopedia. Vol. XVIII. 1905.

- ^ Klickstein, Herbert S. (1959). "Edgar Fahs Smith-His Contributions to the History of Chemistry" (PDF). Chymia. 5: 11–30. doi:10.2307/27757173. JSTOR 27757173. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Bohning, James J. (Spring 2001). "Women in chemistry at Penn 1894-1908, Edgar Fahs Smith as Mentor". Chemical Heritage Magazine. 19 (1): 10–11, 38–43.

- ^ . Collier's New Encyclopedia. Vol. VIII. 1921.

- ^ "Alpheus Waldo Stevenson". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

Stevenson earned his Bachelor of Arts degree from Penn in 1883

- ^ "Taking Action for the Community: The International Students' House at Penn". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

The Christian Association bought 3905 Spruce building from a member of the Potts family (who was a member of the Board of Trustees at the University of Pennsylvania)

- ^ "Global Engagement: The International Students' House at Penn". University Archives and Records Center. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c Franklin, Michael (ed.). "A Timeline of Diversity at the University of Pennsylvania". Archived from the original on July 23, 2019.

- ^ a b McConaghy, Mary D.; Ashish Shrestha. "Student Traditions Rowbottom: Documented Rowbottoms, 1910–1970". University Archives and Records Center. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ Bessin, James. "The Modern Urban University". University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Puckett, John; Lloyd, Mark (1995). Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0812246803.

- ^ "Integrated Development Plan" (PDF). 1962. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ ""'Keeping Franklin's Promise' is the Billion-Dollar Goal," The Almanac, 1989". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "Integrated Development Plan" (PDF). 1962. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c Herman, Edward S.; Robert J. Rutman; University of Pennsylvania (August 1967). "University of Pennsylvania's CB Warfare Controversy". BioScience. 17 (8): 526–529. doi:10.2307/1294007. JSTOR 1294007.

- ^ Lubin, Joan; Vaccaro, Jeanne (September 14, 2020). "AIDS infrastructures, queer networks: Architecting the critical path". First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v25i10.10403. ISSN 1396-0466. S2CID 225026921. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ McCarthy, Charles R. "OEC – Reflections on the Organizational Locus of the Office for Protection from Research Risks (Research Involving Human Participants V2)". onlineethics.org. National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010.

The university was put on probation by OPRR. The Head Injury Clinic was closed. The chief veterinarian was fired, the administration of animal facilities was consolidated, new training programs for investigators and staff were initiated, and quarterly progress reports to OPRR were required.

- ^ Alan Charles Kors; Harvey A. Silverglate. "The Shadow University". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ^ Staff, 6abc Digital (January 14, 2022). "Calls continue for action against Penn professor who made anti-Asian comments". 6abc Philadelphia. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitovich, Jared. "Penn Law's Amy Wax doubles down on racist comments, says she will not resign 'without a fight'". www.thedp.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "ALOK named first Scholar in Residence at Penn's Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Center". March 6, 2023. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ Makdisi, Saree (2023-10-03). "The War Against Palestinians on Campus Keeps Getting More Absurd". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ Maruf, Ramishah (2023-10-25). "UPenn donors were furious about the Palestine Writes Literature Festival. What about it made them pull their funds? | CNN Business". CNN. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ Meko, Hurubie (2023-11-17). "U.S. Investigates Colleges for Antisemitism and Islamophobia Complaints". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY) Questions University Presidents on Antisemitism, December 8, 2023, retrieved 2024-02-14

- ^ Snyder, Susan; Tornoe, Rob; Schneider, Aliya; McGoldrick, Gillian; DiStefano, Joseph N.; Hanna, Maddie; Terruso, Julia; Vadala, Nick. "Penn president Liz Magill faces intense pressure to resign; Pa. lawmakers say Penn Vet funding at risk over her comments". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ Saul, Stephanie; Blinder, Alan; Hartocollis, Anemona; Farrell, Maureen (9 December 2023). "Penn's Leadership Resigns Amid Controversies over Antisemitism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Gallagher, Bryanna (10 December 2023). "Penn president Liz Magill, Board Chair Scott Bok resign amid firestorm over House testimony". WHYY PBS.

- ^ Bok, Scott. "Scott Bok | Penn's next search for a president will be different". thedp.com. Retrieved 2024-02-14.